Global Music Education Movement

The Shinichi Suzuki Memorial Hall in Matsumoto City preserves the home where Suzuki lived from 1951 until his death in 1994. Shinichi Suzuki was born in Nagoya in 1898, one of twelve children in a family that ran what is described as Japan’s first violin factory. Despite growing up surrounded by instruments, he didn’t pick up the violin until he was a teenager, teaching himself by listening to recordings of Mischa Elman playing Schubert’s Ave Maria. At 22, he traveled to Berlin to study under Karl Klingler, a student of the renowned violinist Joseph Joachim. While in Germany, he met his wife Waltraud Prange, and the two returned to Japan in 1928.

After World War II, Suzuki wanted to contribute something meaningful to a country devastated by conflict. He believed music could help uplift the spirits of Japanese children and began developing an approach to teaching that would reshape music education worldwide. In 1946, he moved to Matsumoto to help establish the Matsumoto Music School, which later became the Talent Education Research Institute located next to the Matsumoto Performing Art Center and the Fukashi Shrine.

A Philosophy Built on How Children Learn

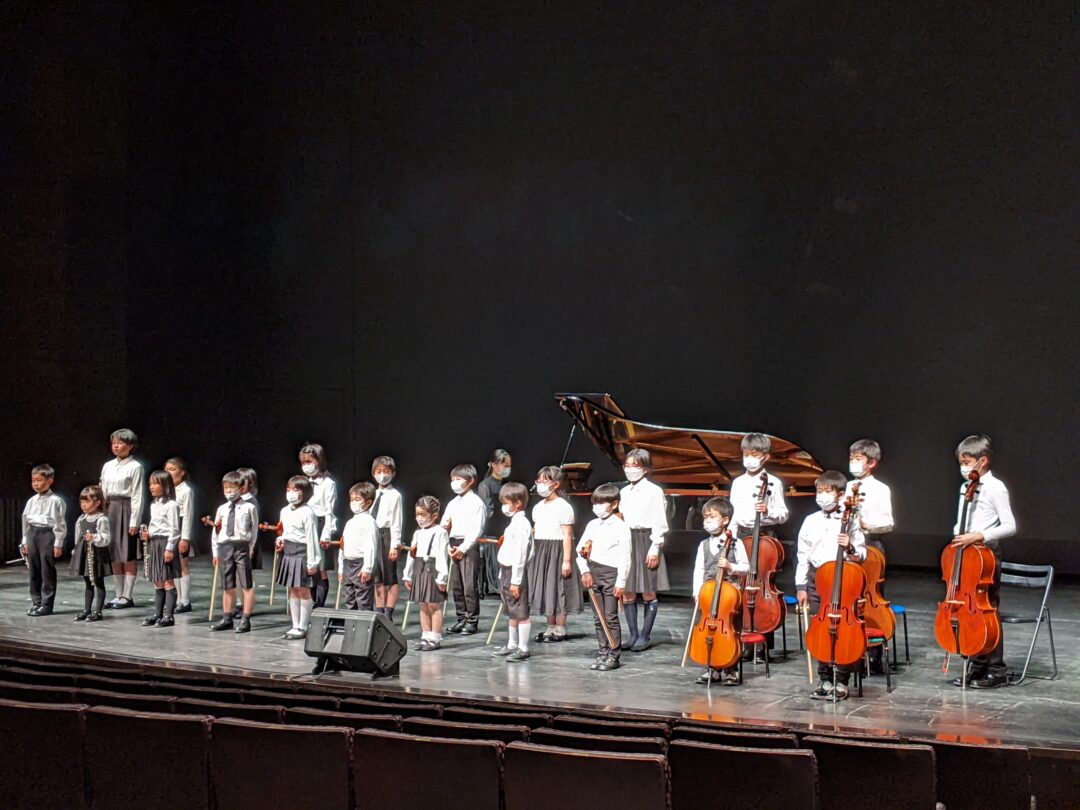

Suzuki’s core philosophy was simple but radical: any child could learn music if taught properly. He observed how effortlessly children learned to speak their native language through listening, imitation, and encouragement from parents. Why couldn’t music be learned the same way? His method emphasized starting young, creating a supportive environment, and treating music education as a way to develop not just skilled musicians but kind, thoughtful human beings. The approach worked. Within years, his young students were performing at levels that astonished audiences across Japan.

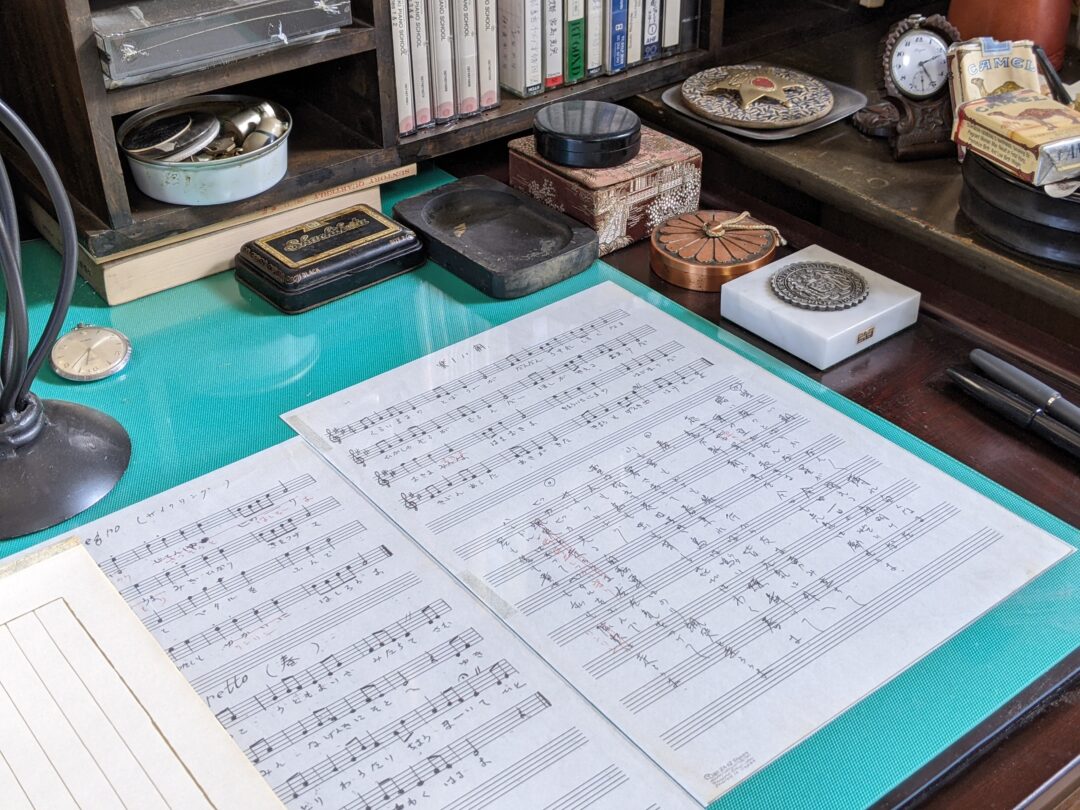

The Shinichi Suzuki Memorial Hall preserves the home where much of this work took place and the house remains much as he left it in 1994. Visitors walk through his workspace, living room, and a memorabilia room displaying awards, photographs, and his violin. The setting is modest and personal—well-worn armchairs in the living room, his desk where he refined teaching materials, letters from Albert Einstein (who befriended Suzuki in Berlin and shared his passion for the violin).

The Shinichi Suzuki Memorial Hall isn’t a polished museum experience. It’s an intimate yet international remembrance of the man who created a teaching method now used in over 40 countries. For music educators and musicians who grew up with the Suzuki Method, the hall offers a chance to see where it all began. For general visitors, it provides context for Matsumoto’s identity as a music city. And insight into an educational philosophy that extends well beyond the violin.

Official Website

- See more Tours & Activities

- Read more Articles

- See more Pictures & Videos